Mason Lieberman: Learning to Play “The Broom”, A Diverse Playlist and, Paying It Forward

Posted by Auralex on 18th Dec 2020

Note: Following are excerpts from the full interview. The interview was conducted by Kevin Booth, Auralex director of sales and marketing. Robb Wenner, Auralex director of artist relations, produces the podcast and jumps in with questions. To hear the full interview, subscribe to Auralex Creative Spaces on your podcast platform of choice.

Interview Transcript:

Kevin Booth: So what drew you to music initially?

Mason Lieberman: I was about, this is a true story, by the way, I was about three years old, and my parents showed me Fantasia, and like all incredibly articulate three-year-olds, I told them that I wanted a broom and they could not understand what that meant because, obviously, they just grabbed a broom out the pantry or whatever and I seemed very disappointed in that. For the following two years, I kept telling them that I wanted a broom. Over time, I got a little older, and it evolved into I want to play with the broom. Finally, I want to play broom, and then eventually, when I was about five years old, they took me to a local Symphony petting zoo thing, you know where they introduce orchestra instruments to kids, and I heard the cello section. I just like stood up and shouted, that's the broom, and all of a sudden my parents were like this little ******** has been asking for a cello! I had private teachers growing up; my first teacher, when I was like five years old, didn't take students that young; she only really taught adults, and she refused to take people that young. She's like, "I will only take him if he's able to sit down and pay attention." I was a very hyper kid, so that didn't seem like that would be in the cards, but something about playing the cello was the one thing that would keep me in control at that age, so she ended up keeping me, and I was her last student.

KB: That's high school age and on, and then you went to Berklee after that?

ML: I graduated high school really young. I was still 16 when I finished, so my parents were like, "don't go all the way to Berklee, that's across the country, you should stay local until you're 18, and then you can do whatever you want". So I got a lot of my general electives and started my music degree at a College in East Texas called Stephen F. Austin State University, and then when I turned 18, I transferred up to Berklee and finished my degree there. I ended up returning to Stephen F. Austin State University for a Masters degree, and I'm now on faculty. Like every millennial, I started playing guitar when Guitar Hero 3 came out because that's where all of us learned to play guitar; it was a lot of fun. I started in my junior year of high school, and I pretty much just sucked until midway through college. Being at Berklee, I noticed more gigs available on all the Berklee gig boards if you were a bassist or guitarist rather than a cellist to make more money and afford not to starve to death, and that was when I picked up the bass. I picked up the guitar more seriously and kind of like built up those skills, and of course, they ended up serving me and helping make the difference. After I graduated, it was a pretty long time before composition and music direction were paying bills, and it was performance and recording. It was working as a wedding cellist or as a touring bassist, things like that, really made the difference.

RW: What was your main study at Berklee?

ML: I was studying video game scoring, so I ended up where I wanted to be. I was specifically a pro music major with a minor in video game scoring because Berklee didn't have a major in it. Shout out to Michael Sweet, the MVP's best faculty at that school.

KB: At what point did you decide this was a potential career path, or was it always a career path?

ML: This was always what I was going to do. There was never really anything resembling a backup plan or other fall back plan. Not having a fall back plan is mostly indicative that I had a lot of support growing up. No five year old can just start playing cello! I could only get into the sort of stuff that I grew up on with a family that believes in the arts and supports the arts. It's one reason that I'm such a big proponent of music education and literacy and making sure that people have an opportunity to go into this field because it's challenging if you don't have that kind of grounding and basis. It's a challenging field to make any kind of living in.

KB: Are there any musicians and composers that influenced you greatly as you were getting your start?

ML: Anything that my dad listened to, I listened to. I was a huge fan of the band Chicago, and I grew up on film scores by John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, and all the greats. On the rock side, I was always a huge fan of Dave Growl and the Foo Fighters, Soundgarden, and Chris Cornell. Even though it sounds nothing like my speaking voice, a lot of why I get hired as a vocalist is doing like Dave Grohl type stuff. I had a backward path into rock vocals because I was really into musicals growing up, so like the legit-style singing, like Jazz, came naturally to me. I was just driving home one day, in my early twenties, right after college, and I was just jamming along to a song, and I felt some phlegm cleared in the back of my throat, and I was like, "oh, I can hit that now!"

KB: Are there any other genres or other influences that you would like to mention?

ML: Musically, I'm just like a polyglot. I love everything. I like to listen to a lot of music to improve my vocabulary. I think that an excellent media score is just storytelling. I believe that most good music is just storytelling, but in particular, with media scores, you are pursuing someone else's vision. Different things influence someone who probably had different life experiences than you growing up and comes from another place in the world. If you want to score their experience and fill that space appropriately authentically, you must take pieces from everything. I listen to Tamil rock, and I listen to Korean pop, I listen to African percussive stuff, I'll listen to Flamingo, I'll listen to Jazz, I'll listen to anything. Not only to be authentic in what you're doing, but just to be able to connect to the audience as a whole, you need to take into consideration precisely that. You have to try and go after the different experiences that all the different people in your audience you're going to have and make that score effective. By nature of the fact that I do so much work with East Asian music, I kind of owe it to the listeners and the people who play the games and watch the shows that I work on, to know as much about those harmonic styles and culture. No one wants like a dude who comes in and writes like, Butt rock. Every culture has unique music and has a really rich heritage for how their music ended up the way it is. If you're going to write in those styles, it behooves you to listen to them and spend time studying and analyzing. My style is culturally respectful, plus a little bit of like funk groove, plus way too much Butt rock!

KB: How did you get involved in scoring for games?

ML: Professionally, I started with animation. My career trajectory starts the way I think every single music graduate starts, which is that I did not manage to secure an internship after graduating. I had zero job prospects since I didn't know anyone, but after three months of unemployment, I posted on Facebook that I guess it's time to apply for Guitar Center because at least they'll understand if I have a gig. That's where my story kind of took a turn because I never studied with him while I was in college, but I built a relationship with a composer that worked with Roosterteeth, a fellow named Jeff Williams. He writes for the anime-influenced series RWBY, and he reached out to me and kind of changed my life. He said, "I don't see why you'd want to work for Guitar Center when you could be working for me," and that was my first real gig in that regard. I recorded on his show at that point already as a cello player, so we were friends, and we had done live gigs down in Austin (TX) and stuff, but I had never worked as a media composer on a TV series type of thing. That was 15 to 17 minutes of music every week, and getting to do that taught me a lot; and RWBY happens to be a very popular series in the anime gaming world, and that broke me into the Japanese market. When I left RWBY, after season three, I was the only RWBY composer that was at least moderately able to speak Japanese, and I was available for work, and that's kind of what led to me getting the call for the Beyblade series.

KB: So you were ready when the opportunity arose?

ML: I will always tell people to curate the work that you do because every single gig that you take, every single project you work on, everything you record, that is your entire reputation. People tend to only pay attention to the last thing you did or the most significant thing you did, and you never want to put out mediocre work. That's one thing where I differ from a lot of people, in that I'll tell them that if you don't think you're the right person, say no to the gig and then turn around and recommend someone else. I guarantee that you will get more work out of having made a successful referral from both that person and the company who you solved the problem. I think that a lot of what I've got to do has come from some of the things that I said no to, but the person who I helped connect to that gig did a great job, and then that person trusted me for other projects or that company knew that I could still curate things for them and that made a difference. The most important thing you can do is to leave the industry a better place than you found it. If something was hard for you, make it easier for the next person. Find a way to get someone else that first gig and help someone out makes our industry a little bit warmer and, a little smaller, always helps at the end of the day.

KB: What project are you most proud of?

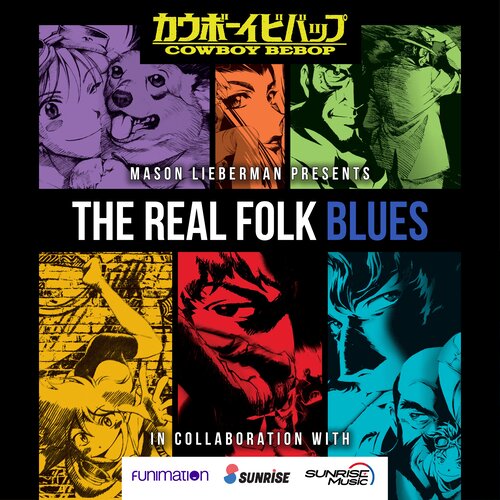

ML: I have to say one of the things that I'm most proud of isn't even one of my paid gigs. It's some charity music I got to do this year, right when Covid-19 struck in March. I realized that many of my friends are touring people, and you could never get them on a track if you tried, so when the touring industry shut down, a lot of those people were suddenly available, and they were out of work and in locked at home. None of us had anything to do, and we were in a holding pattern. I was fortunate that I got to keep my job. However, things were still slow from a production side for us, as companies figured out how this was going work, so I decided to put together a big arrangement and just cover a song that felt appropriate for the moment. I happened to pick The Real Folk Blues from the legendary anime series Cowboy Bebop. The series has an incredible jazz soundtrack by composer Yoko Kanno, one of the Queens of Japanese media. I started putting together a group of artists who I love collaborating with regularly. These people represent the game industry. Over 45 days, it went from an idea that I had on Facebook to a fully arranged, recorded, mixed, and mastered track and partnering with the original studio that created this series release it on vinyl. We also got the original series composer, Yoko Kano, and her session band, the Seatbelts, some of the top session players in Japan, to be on this track. It was released on May 1st and sold a little under 3000 vinyl in one month, and we raised $50,000 for Covid relief for the CDC Foundation and to Doctors Without Borders.

KB: Your room is standard in some ways in that it's a bedroom in a home.

ML: We did some things a little unconventionally. I'm grateful for all the changes that we managed to do because I think that even though I work on all these franchises, I'm really working in the same space every bedroom producer in the world is working out of right now. The room is the same 10' by 13' wood box type of situation. There is a giant window that you can't do anything about and a door that isn't really in the position that you would want the door to be in, and an air conditioning vent you can't do much about. We had to do some wizardry to make this place transform from a stuffy, small box into a surprisingly competent mix and recording space that I can use on all of these properties in the middle of Covid-19. One of the challenges was a complete closet with mirrored doors on it. We faced (the mix position) towards the closet to use the closet, with the doors off, that your design suggested. I adjusted a couple of the ProPanel™ positions based on some of the gear I needed to keep within the closet. I really love my studio, and it sounds awesome. The treatment in the closet is working as a base trap on the front wall. The ProPanel™ Ceiling Panels make such a difference. I think we did a great job and I'm grateful for you guys and thank you Auralex!

For more info about Mason Lieberman, go to:

https://www.masonlieberman.com

https://www.facebook.com/MasonLiebermanMusic

https://www.linkedin.com/in/masonlieberman/